How to Decide if You Should Do a Webcomic

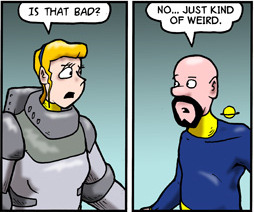

Let's face a few facts: Webcomics are new. A lot of people think webcomics suck. An enlightened subsection of those know better and assert that only the majority suck. This does not speak highly of the ones who actually want to get good at it. Granted, you could say the same things for a lot of internet groups, but let's assume you actually are looking to do something with webcomics, in spite of all this.

You SHOULD do a webcomic if:

- You have a story to tell (with some visual nature to it). If you find yourself cooing endlessly about the moons of the planet Mazz'zel'ta and the way they shine in the darkness, or other striking visual effects, go ahead and start drawing it.

- You want to expand your art portfolio. Know what's big in portfolios? Related Works. Pages in a story are as related as related works get, and are more likely to test your boundaries as an artist. As a bonus, it pretty much ensures that if someone on DeviantArt or elsewhere sees one page and likes it in the least, they'll probably read the other pages as well.

- You don't feel 'ready' to pitch your idea to the "Big Boys" yet. You'll probably never feel ready, but at least you can start working on it now and gaining fanbase instead of waiting for letters from them (rejection or otherwise).

- You want to start making money off of your art. It won't be much money, but if nothing else it should improve your work and expand your audience enough that you can eventually start taking commissions (and now people will actually want to buy them!).

- You feel there's a gap in the webcomics already out there. If an anime about baking bread can get taken seriously, anything can. As a bonus, think of all the new fans you'll get for covering a topic they care about. In the meantime, I'm just going to say this outright: I would LOVE to see a webcomic about crochet, or possibly knitting.

- People keep telling you to start a comic. Hey, you've already got a fanbase, why not? Motivated fans you can actually have a cup of coffee with are rare enough that even just one or two of them is reason enough to give it a try.

- You ever plan on doing a comic 'eventually'. Just start now. Seriously. Worst case scenario, you ditch working on it to start a new one.

- You expect to make LOTS of money off your art. It doesn't work that way. The only truly 'successful' comics I've seen have been at it for years, and when making just above the poverty line in donations alone is considered 'successful', that means you're probably not going to become a millionaire doing this.

- You think "I don't need ____! So-and-so did this, I can too!" Whoever you're holding in high regard did it better because they know what they're doing and how whatever rule they're breaking is meant to be broken. You don't. Don't try it until you do.

- This goes double for people trying to imitate stick-figure comics. Yes, good writing can eclipse bad art. This, however, assumes good writing.

- The story you want to tell is fanfic. Come back when you have some originality and aren't a walking copyright violation. At the very least, tweak it until it passes the "I think _____ did it better" test.

- You plan on using Sprites / Screenshots / Other Game-Originating Material in Lieu of Art. No publisher will EVER touch these types of comics with a ten-foot pole. Besides, it's pretty limiting as far as visualizations go. If you insist on doing it, fine, but don't expect it to go beyond being a webcomic unless you can find a way to make the rest of the comic shine in comparison.

- You plan on hosting the comic at ComicGenesis, SmackJeeves, DrunkDuck, or any other "Webcomic Hosting Specialist" for the life of the comic. It screams "Ameteur wanted Free Space!" and is the webcomic equivalent of GeoCities. Starting out on free space isn't bad in and of itself, but the top Comic Repositories have bad enough reputations that you may be better off doing it yourself and avoiding the taint. For God's sake, if you're going to seriously start a comic, get a halfway decent webpage; if you have any readership at all, you can make the money from hosting back in ads alone. If you MUST be a cheapskate about it, go with ComicGenesis, as you have the most control there and the least-stupid name in the URL. Barring this, LiveJournal and Blogger work as well, provided you use an additional image host like Photobucket. DeviantArt and other Art repositories are also good.

- You're only making the comic to impress people. Don't. They're not. You probably won't become famous for doing this, and if you do, it'll be so many years from now that if this is the only reason you're doing it, you'll kill yourself before you ever get that far.

- You don't plan on drawing a comic for very long (and I mean in terms of updates, NOT time-per-page). Comics are a BIG time investment, and take years of updates and tons of strips to take off. If you don't have the time, do a short story, but starting a comic and then not being able to keep it up is terrible and pisses off whatever fans you've acquired.

Labels: comics, content, starting out, tips